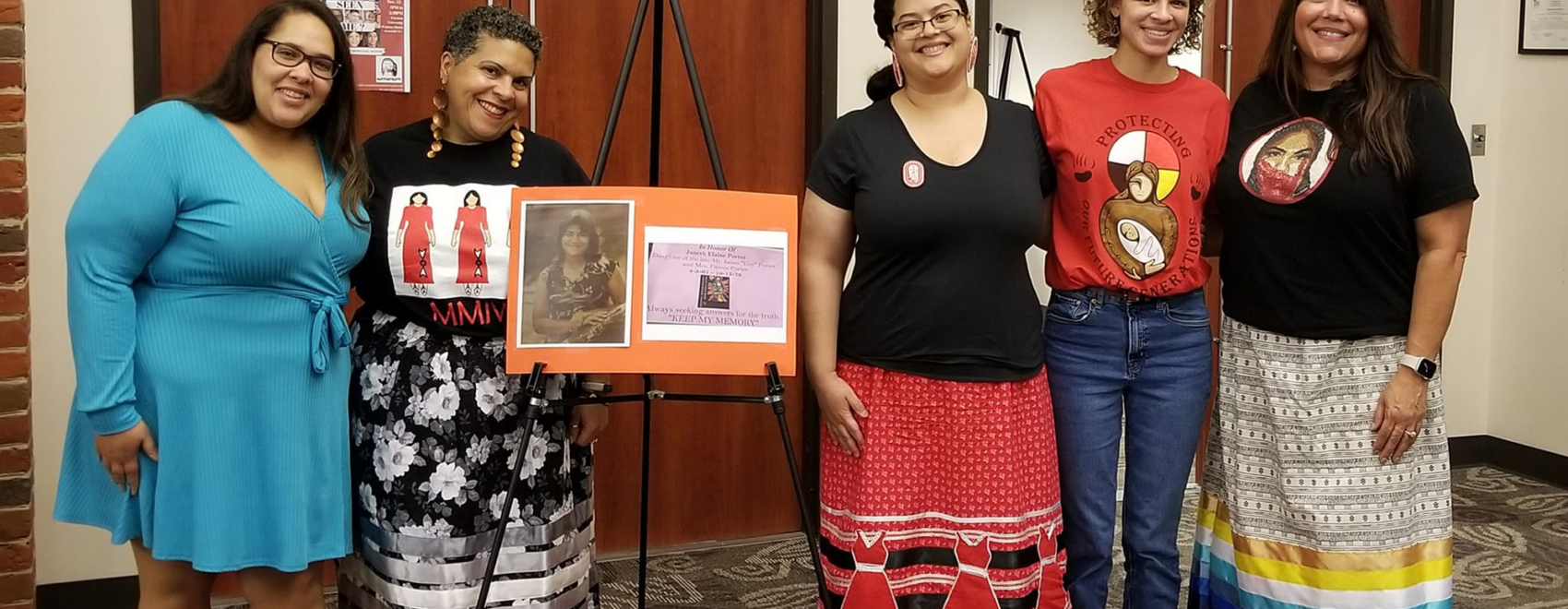

Raisa Jones and Melissa Harris. / Credit: Jennifer Brewer-Young

On a Saturday afternoon in November – Native American Heritage Month – a panel of women from tribes throughout the Carolinas came to the Watkins Room in the Trone Student Center to raise the alarm about a crisis.

Native Americans, especially women and girls, are being taken from their homes and families at an alarming rate, said the panelists, representing the Murdered and Missing Indigenous People (MMIP) movement working hard to spread the message across the continent.

It’s an undeniable crisis, and a nearly invisible one, said Chloe Sanderson ’24, who organized the CLP event that brought the women to campus.

“Our numbers are staggering,” she said.

More than four out of five Native American and Alaska Native women (84.3%) have experienced violence, according to a report from the National Institute of Justice; more than half have experienced sexual violence (56%). The rates of murder, rape and violent crime are all higher than the national averages, said Sanderson, a member of the Lumbee tribe.

The statistics likely don’t tell the whole story: The race, citizenship or ethnicity of Native Americans is often recorded incorrectly on death certificates and law enforcement records.

“There’s a lot of misinformation out there,” Sanderson said. “We’re being misidentified and misclassified.”

In addition to spreading awareness of the crisis, “the MMIP movement really strives to explore overall themes, like what’s happening in the criminal justice system that’s failing people,” she said, adding that the lack of media attention and public awareness aggravates the crisis and frustrates the search for justice.

The panelists for “Have You Seen Me? Missing and Murdered Indigenous People” included Niki Locklear, a member of the Lumbee tribe and the program director for the domestic violence and sexual assault program for North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs; her colleague Raisa Jones, the Lumbee advocate for the commission; Vivette Jeffries-Logan, a member of the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation and a longtime advocate for domestic violence issues; and Melissa Harris, tribal administrator of the Catawba Nation, who works with children’s services but has personal experience with MMIP issues. Katherine Kaup, the James B. Duke Professor of Asian Studies and Politics and International Affairs, was moderator.

Sanderson, a health sciences major from Charleston, South Carolina, who plans to study criminal psychology, said she has been concerned about the crisis for a while.

“This is something that ties directly into both my ancestry and my career interest,” she said.

It’s difficult to raise public attention and concern, Sanderson said. Indigenous voices are often not heard in part because of widespread ignorance about the present-day realities of Native American people.

“We’re still here, and a lot of people don’t understand that,” she said. “Indigenous people aren’t just something in a history textbook. We’re standing in front of you, and we’re telling you there’s an issue.”

Generational trauma, passed down from grandparent to parent to child among indigenous populations, can perpetuate the silence and hinder the search for justice, said Sanderson. “If your parents didn’t speak up about the abuses they were experiencing, you begin to think that’s normal,” she said.

After awareness, Sanderson said, the next step is getting involved and staying informed. For the CLP event, she gathered extensive lists of regional resources and federal and national organizations involved with the issue.

The panel discussion’s success has encouraged Sanderson to plan more events.

“I am hopeful for the future, because all it really takes is for you to show up,” she said. “You have to put yourself in a position where you can hear these things and you can begin to care, because if you don’t show up, you’re not going to know. People are dying. People are being taken from their homes and families left and right. If you can’t care about that, that’s shocking to me.”